Warner Brothers’ house style during the 1930s embraced gangster films, along with the occasional big production musicals. During the Pre-Code years of the early 1930s, those gangster films were gritty and violent and made James Cagney (THE PUBLIC ENEMY, 1931) and Edward G Robinson (LITTLE CEASAR, 1931) big stars. But once the production code became enforced during the second half of the 1930s, the studio made more melodramas and story-driven action films. Productions were becoming more grand, more dramatic, and more expensive.

While Cagney wasn’t walking off the Warner lot following a contract dispute, he was a major bankable star for the studio. Cagney ended his contract with Warners in March of 1936, made a couple of forgettable films with Grand National Pictures, then started a new contract with WB in January of 1938. He was a valuable star because he was very talented in a multitude of assets. We often think of him in connection to his little tough guy image, but he was an actor with great range and a nice hoofer in musicals, too (FOOTLIGHT PARADE (1933), YANKEE DOODLE DANDY (1942), etc.)

Today, we’ll be screening Cagney as one of those tough guys- but with a great deal of range. His performance in Michael Curtiz’s ANGELS WITH DIRTY FACES (1938) earned him his first Oscar nomination.

Curtiz is said to have favored underdog stories, especially themes of self-sacrifice and redemption. We will see these themes on full display in this feature. This film takes on several themes and tones. It is a crime drama, and one that communicates via physical media. Typical Warner Brothers films love to rip stories from headlines or feature a newspaper reporter. Much of the plot highlights are told via headlines in ANGELS WITH DIRTY FACES. Additionally, we see a radio truck at the beginning that projects music and headlines via speakers and that truck is seen later in the film, too.

This film may be a crime drama, but unlike many stereotypical gangster flicks, this goes deeper with social commentary. To pass production code, there must be a sense of redemption for the villain. A change of heart. A reversal of morality. We’ll discuss if that was accomplished in this film.

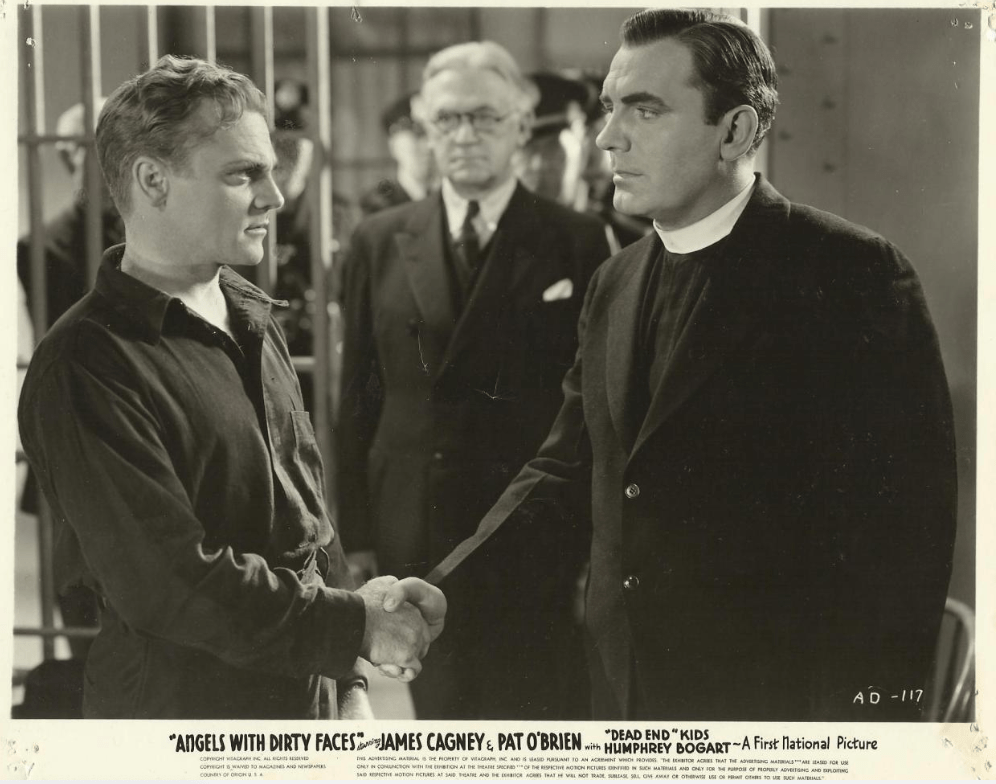

Another theme deals with duality. This idea that two close characters split- one going down a path of good, another towards bad- is not new. And it would go on to be repeated in several films. Here, the prologue of the film starts early in the lives of two kids. We see youngsters that are poverty-stricken, just getting by in a feral way, with no parents in sight. It’s strictly a matter of survival and the setting is the Great Depression. They hop trains to escape, attempting to not get caught by authority. We see “Rocky” get caught, while “Jerry” slips away. Which leads to very differing paths= only one spends years hopping in and out of the criminal justice system- starting as a juvenile delinquent for petty crimes to bigger crimes (and bigger jails) as an adult. A career criminal (James Cagney as “Rocky Sullivan”). The other becomes a priest (Pat O’Brien as “Father Jerry Connolly”).

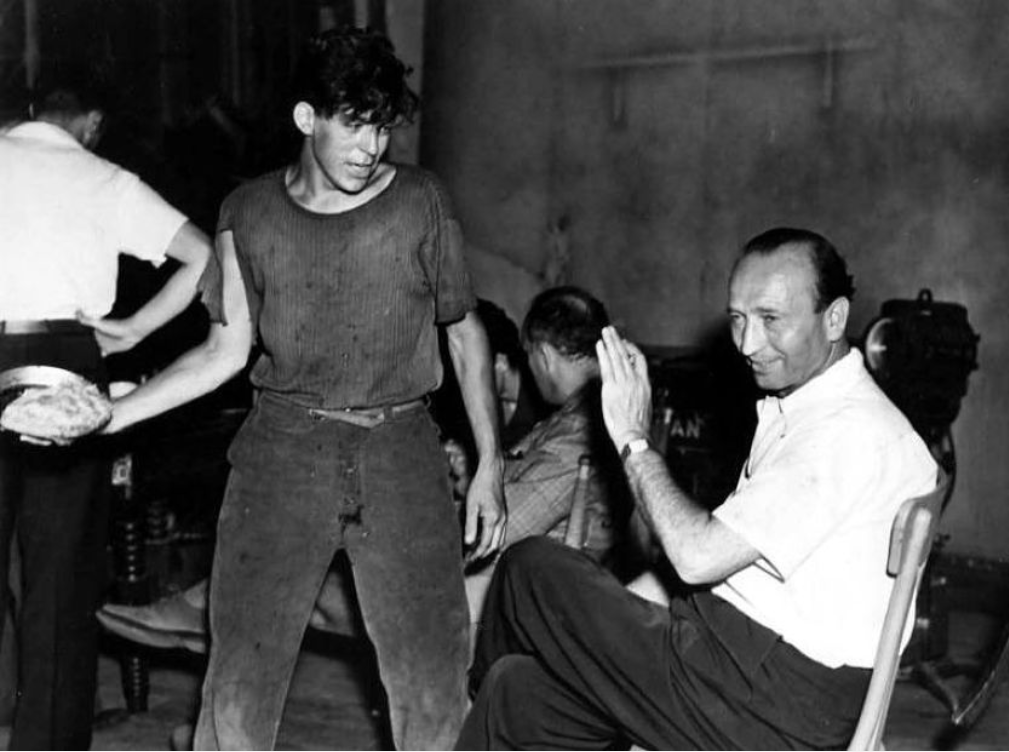

This vital prologue that takes us through the background stories of these characters in their youth and how they became who they are as adults was almost cut from the film entirely. They were beginning to run behind schedule (not common for Curtiz, especially so early in the process) simply because they couldn’t find the ideal young actors to portray a young James Cagney and a young Pat O’Brien. They settled on a solid look-alike for Cagney but a youthful doppleganger for O’Brien was proving difficult. Curtiz was feeling pressured to cut the prologue entirely, but thankfully they forged on and kept this informative plot segment intact. Filming began June 27, 1938 and completed August 10th, with the release in November.

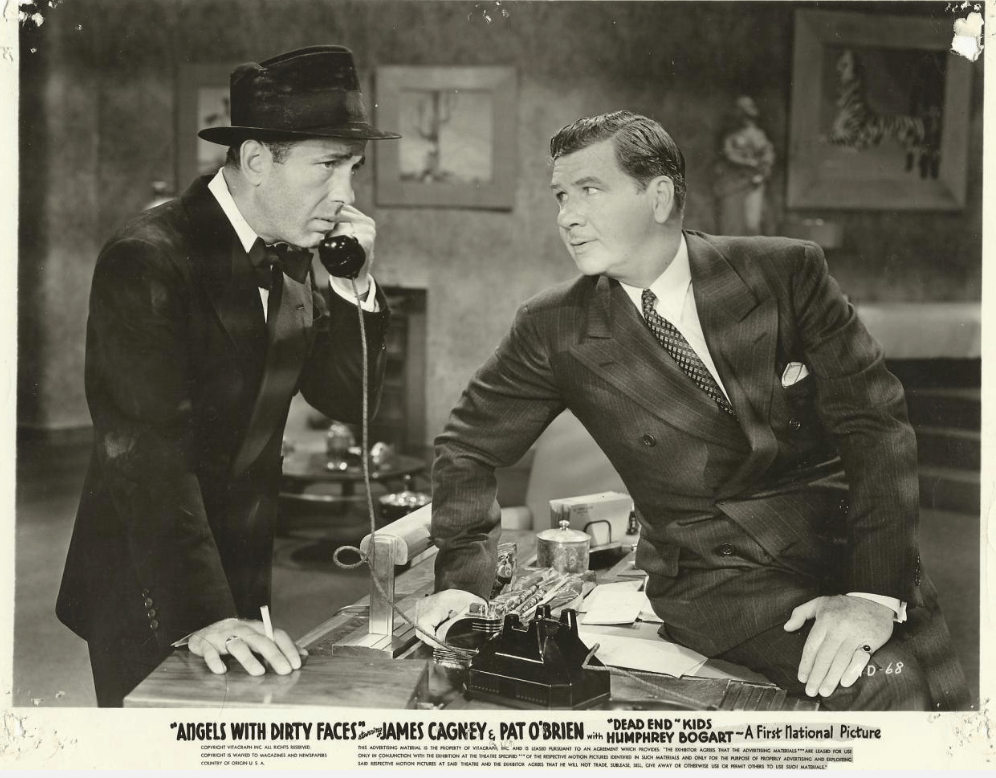

Another theme we see early in the film is that of an exile who returns home. Rocky, who ran the streets with confidence since his youth, returns home after years of incarceration, and is now the outsider. Both Rocky and Jerry are connected- not only from their childhood friendship, but in their Irish Catholic roots. When Rocky returns, he notices that his soloist hoodlum ways that once ruled his neighborhood have changed. Now it’s no longer petty criminals on the street that hold the power- it’s organized crime. It’s bigger money, more sophisticated, and more corrupted into the legal system.

According to biographer Alan K Rode, Cagney’s new Warner Brothers’ contract was: for five-years, he agreed to do a dozen films at a pace of two or three annually, he’d receive $150k per picture, plus ten percent of the gross if over $1.5 million, script approval, the ability to suggest his own story ideas, twelve weeks (consecutive) of vacation, his brother William would serve as associate producer on all his films, and a “happiness” clause that meant he could bail out if a relationship turned sour.

Based on an original story by Rowland Brown, Brown took his story to Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur to finesse. Hal Wallis then purchased it for $12,500. Curtiz was assigned to direct because of fears that the Cagney brothers would need a strong personality to keep control. As a result, this picture has stronger character development, complexity of story, and more heart than the typical gangster tale. Warren Duff and John Wexley were assigned to adapt the screenplay. As one would imagine, a violent film about morality and the friendship between a gangster and a priest would be watched closely by Joseph Breen and the production code.

To keep key scenes from being cut by the censors, the Cagney brothers manipulated Curtiz at every turn with artistic suggestions. In the end, more was kept in than would normally be expected. Generally, Hal Wallis was not a fan of changes (especially if running over schedule and/or over budget), but there were examples of changes (added scenes where part of a new set needed to be built to accommodate the beefed-up scenarios) that Wallis looked the other way. Partly when he agreed that it was beneficial, or if Cagney was the one who suggested it (as his new contract allowed it).

This hardworking yet creative energy on the set worked well for both Curtiz and the cast. With one exception with the “Dead End Kids.” The youngsters would frequently prank and horse around on set. Cagney stopped this after a scene where Leo Gorcey was behaving cocky and ad-libbed a line to Cagney. He hit back, with a real smack, and firmly scolded Gorcey to cut it out. The cast never had issues after that, and the kids stayed true to the script. The Dead End Kids began on Broadway as a youthful group from the streets (Billy Halop, Bobby Jordan, Huntz Hall, Leo Gorcey, Bernard Punsley, and Gabriel Dell), then contracted with Sam Goldwyn for a film with that same moniker, “Dead End.” Warner Brothers bought out their contract to make ANGELS WITH DIRTY FACES and kept the name. Most old movie fans are more familiar with their more prolific name that was yet to come, The Bowery Boys. Inclusion of the ‘Dead End Kids’ turned out to be a critical plot driver that allowed the full circle of the story to make sense, and heavily enhanced the sub-story of criminal influence on influential youth.

One of the most enduring themes questions the effect of criminal influence on children, and the concept of nature vs. nurture. Which is why many think of this as a favorite of all the Cagney films and crime dramas. The social messaging remains rather timeless.

Curtiz, in his high-risk methodology, created a scenario that nearly took out its star. And this wasn’t the first time for Cagney and Curtiz. In blocking a warehouse scene with an active spray of gunfire, Cagney insisted that blanks to be used. No live ammo. This is because the same marksman on the set of THE PUBLIC ENEMY came too close for Cagney’s comfort, a bullet barely missed him. This time, Cagney insisted a process shot be edited in later. This time, Curtiz agreed, reluctantly. When they set up the live ammo shot to film the glass breaking, a stray bullet accidentally hit the steel window frame and ricocheted back to Cagney’s mark, right where he had been standing moments before.

For Pat O’Brien, he shared another example of the high risks that Curtiz would take with actors to get the most realistic shot on camera. In a scene with the young actors who portray the younger versions of Rocky and Jerry, the actors run across railroad tracks and Jerry slips (we see his ‘scar’ across his forward when O’Brien portrays the adult Jerry). The falling was choreographed. What remained unknown was communicating these details to the train engineer whose rushing train barely missed the boys. From Rode’s Curtiz biography, O’Brien recalled, “The train barely missed hitting the two boys, who leaped aside like salmon. The shaking engineer clambered down out of his cab; he looked like death at bargain prices. Mike, a true Hungarian, just smiled at him. ‘Very good. This was part of the action of our story. I purposely did not tell the two boys before you go so fast.’ The film crew had to restrain the train engineer from attacking Curtiz, who shook his head afterward and asked, “How do you get realism if not take chances?”*

To achieve another type of realism on set, Curtiz built up an impressive four city blocks slum set that brought in over fifty fruit and vegetable carts (with real produce) from New York, a large cast of extras, and clothes lines draped everywhere. This attention to detail can be seen not only in this early scene, but also when we revisit this same neighborhood set when almost two decades have passed. The headlines tell us we begin in 1920 and return in the late 1930s. If you look closely, you can see realistic changes that are just the right authentic touch.

With a strong cast, the original story by Brown, and the masterful direction by Michael Curtiz, it’s no wonder that ANGELS WITH DIRTY FACES earned three Oscar nominations- Cagney for Best Actor (he lost to his fellow ‘Irish mafia’ pal Spencer Tracy for BOYS TOWN), Rowland Brown for Best Writing, and Michael Curtiz for Best Director. Additionally notable are the contributions of cinematography by Sol Polito (who worked with Curtiz on nearly every successful film Curtiz directed at Warners, plus other top directors), and music by Max Steiner. This was a banner year for Curtiz. ANGELS WITH DIRTY FACES cost the studio $633k but made $2.3 million. This is following the big success of Curtiz’s FOUR DAUGHTERS in the same year, which was also a financial and critical success and earned five Oscar nominations.

Cagney’s inspiration for Rocky’s twitching shoulder rolls and distinctive “what d’ya hear, what d’ya say?” was plucked from a real person from his childhood, a drug-addicted pimp who would stand on a corner in the neighborhood. He later grew to regret utilizing this characterization as it became a typecast for Cagney impressionists for the rest of his life.

In today’s discussion, let’s review:

-What themes do we see? Duality, criminal influence, childhood delinquency, the challenges and societal responsibilities of poverty, personal integrity, violence and its influences and aftermath, hero worship and its downfalls … Does this film serve as a lesson in morality- or a societal warning?

-If Rocky is a bad guy, is he 100% bad, or are there shades of complexity? Do we feel sympathy or pity for Rocky? Was Rocky savable?

-Was Rocky’s true crime getting caught in his youth (as compared to Jerry) or would they each follow their same paths regardless? What if the roles were reversed?

-If Laury (Ann Sheridan) was raised in the same neighborhood as Rocky and Jerry, why did she not follow the same path? Was her preference in men a reflection of her upbringing combined with being a woman? Are the fates of both her dead husband and of Rocky, and their criminal careers, a poor reflection on her choices or a doomed demographic? What do you think happens to her character after the story ends?

-In the end, does Father Jerry really boot out all the corruption of his town? Do the kids find a change of character- or simply find a new hero to worship?

-Look for those Curtiz touches including artistic camera movement and shadows. The last scenes at the prison are truly impressive—both with beautiful camera work and in Cagney’s performance. He claimed that in that emotionally intense final scene, it took several days to shoot and he lost four pounds. Did you find it moving?

Cast and Crew:

Director- Michael Curtiz

Produced by- Samuel Bischoff (producer, uncredited), Hal B Wallis, Jack L Warner (executive producers, uncredited)

Writing credits- Rowland Brown (original story), John Wexley, Warren Duff (screenplay), Ben Hecht, Charles MacArthur (uncredited)

Cinematography- Sol Polito

Music- Max Steiner

Art Direction- Robert Haas

Editing- Owen Marks

Costumes- Orry-Kelly

James Cagney (1899 – 1986)- Rocky Sullivan

Pat O’Brien (1899 – 1983)- Jerry Connolly

Humphrey Bogart (1899 – 1957)- James Frazier

Ann Sheridan (1915 – 1967)- Laury Ferguson

George Bancroft (1882 – 1956)- Mac Keefer

Billy Halop- Soapy

Bobby Jordan- Swing

Leo Gorcey- Bim

Gabriel Dell- Patsy

Huntz Hall- Crab

Bernard Punsly- Hunky

Joe Downing- Steve

Edward Pawley- Edwards

Adrian Morris- Blackie

Frankie Burke- Rocky as a boy

William Tracy- Jerry as a boy

Marilyn Knowlden- Laury as a girl

John Hamilton- Police captain

Dickie Moore- Child soloist in boys choir

Sources:

“Michael Curtiz, A Life in Film.” By: Alan K Rode. University Press of Kentucky. 2017., Imdb, Warner Brothers Archive bonus material

Love it, Kellee! (And I have been revisiting a lot of Cagney films this summer! Including ANGELS WITH DIRTY FACES twice.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful! And thank you!

LikeLike